MISSION REPORT IN GATUNDU. KENYA

SPANISH TEAM

NOVEMBER 2024

On this occasion, our team has carried out a new cooperation mission in Kenya. Specifically at the Level Five Hospital.

The Gatundu District Hospital is classified as a District Hospital. It is a Public Hospital owned by the Ministry of Health. It is located in the Gatundu constituency, Gatundu South division, Gatundu sub-county in Kiambu County in Kenya.

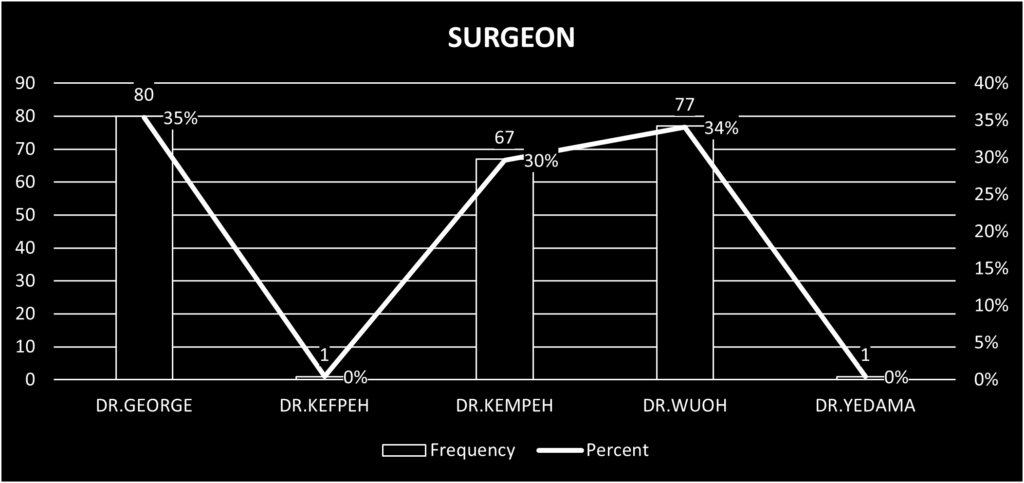

Our team this year consists of a total of 12 people: 6 general surgeons, 3 anesthesiologists and 3 nurses. All of us with extensive surgical experience and some of the veterans with more than 10 cooperation missions previously. Two of the surgeons are pediatric surgeons, given the previous indication by Dr. Mwitta (local surgeon), that he had enough child patients to operate on.

The mission took place between November 9 and 16, 2024.

We arrived at Nairobi airport on Sunday 17 at 03:15h, coming from Madrid and Barcelona, via Istanbul on flights without incident.

At Nairobi airport we had the first and important incident: the customs agents at the airport blocked the 23 boxes of clinical material and medicines, claiming that they had no knowledge of the list of material or authorization for entry into the country, so they blocked all the boxes. After endless negotiations on the night of Saturday to Sunday, the material was left in storage at the airport until Monday. The human team went to the hotel, leaving one of us at the airport waiting for events, which never happened. On Sunday morning it was impossible to solve the problem, due to the absence of a responsible official to sign the import document.

This circumstance, which was delayed until Monday morning, meant that it was practically impossible to begin surgical activity until Monday afternoon. On Monday morning we triaged the patients until all the clinical material arrived at the airport. The intervention of the hospital director was necessary, who went to the airport with Dr. Marsal and after a lot of paperwork, a lot of posturing and little collaboration on the part of the officials, they signed the long-awaited paper, after paying some fees, which the hospital management took care of.

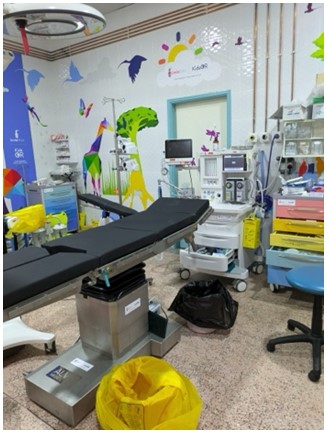

In principle, we brought material and human equipment to be able to work on 3 simultaneous surgical tables. Because there are only 2 operating rooms available, an operating room with two surgical tables was set up.

The hospital has only 2 anesthesia machines and non-centralized O2, so one of the operating rooms was dedicated exclusively to pediatric surgery with general anesthesia, and the other operating room (double table) was used from Tuesday for adult surgery, with locoregional or general anesthesia.

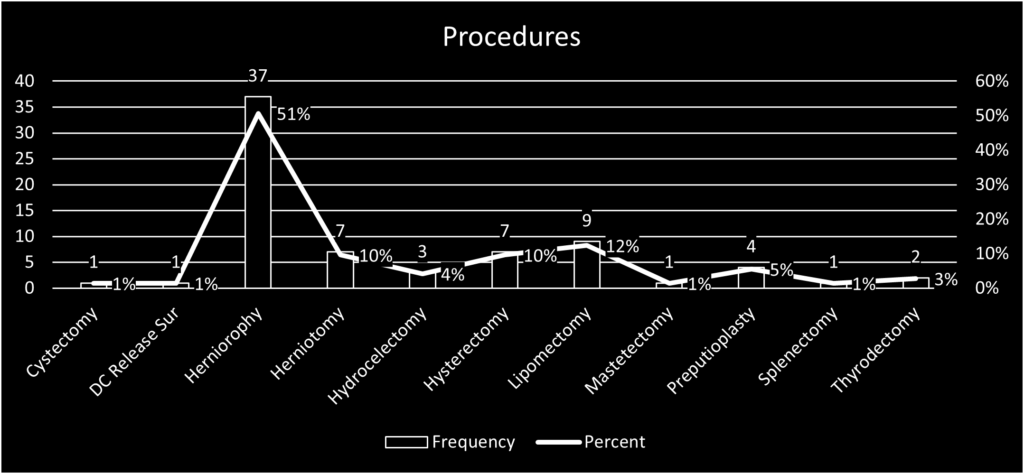

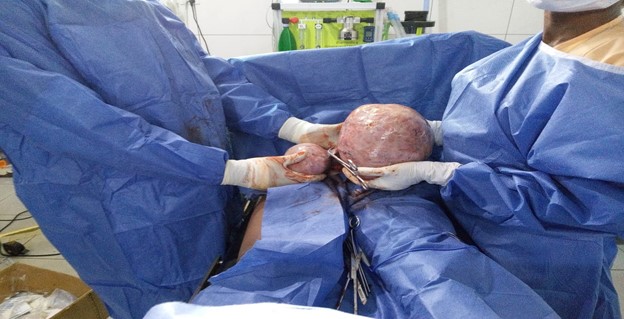

In total, 56 patients were operated on and a total of 67 surgical procedures were performed from Tuesday to Thursday. There was only one early complication, consisting of a hematoma of the surgical wound in an adult, which was reoperated on the next day after the patient was visited, and was resolved.

Most of the patients spent the night in the hospital, and except for some patients operated on for hernias who stayed one or two days for pain control, and eventrations, all the others, including the children, went home the day after surgery. So far and according to the information given to us by Dr. Mwitta, there have been no incidents or complications in the medium term for any patient.

On Friday 15th, no surgeries were performed due to lack of patients, so our activity that day was to visit all the patients from the previous day and verify the absence of early complications and discharge the patients.

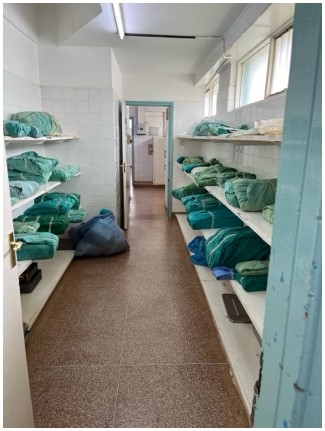

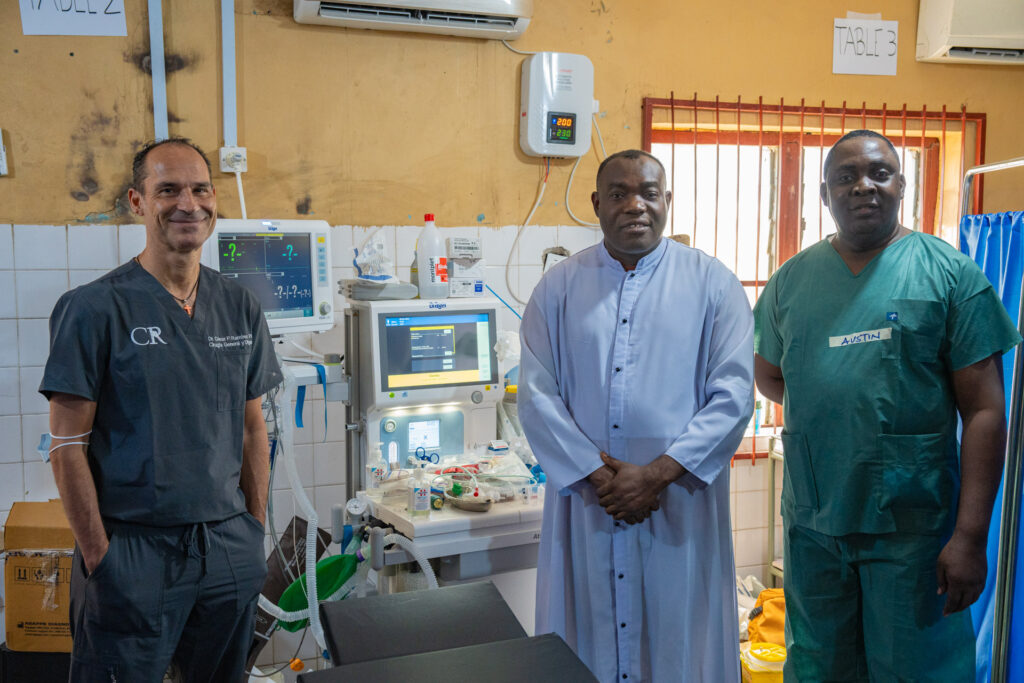

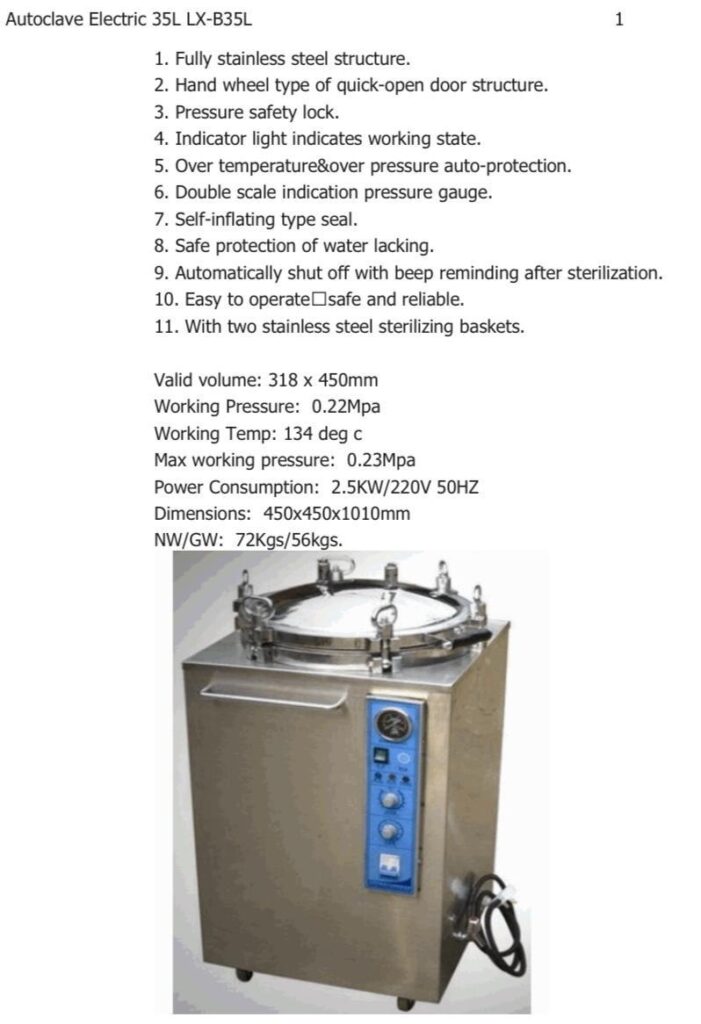

Thanks to the good work of our colleague Dr. Marsal, we were able to acquire an electric scalpel, which was donated to the hospital (they only had 2), and an autoclave, which arrived at the hospital on the last day of the mission. When we arrived, the autoclave was broken and it was necessary to take instruments and consumables to another hospital, which delayed and hindered the fluidity of the surgical activity. Photos of both are shown, and a video of thanks from Dr. Mwitta

Our stay at the hospital ended on Friday at 12 noon local time, and the team left for the capital Nairobi where we stayed in a hotel. The next day part of the team left for the return trip to Barcelona, and 8 of us went to the Amboselli National Park, for a few days of rest and enjoyment of the wonderful natural reserve at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Comments of interest for future missions:

Level 5 Hospital is a regional hospital with many years of antiquity and poor maintenance. The surgical area is suitable for this type of mission, but the infrastructure is scarce. The consumables are poorly organized and much of the material is expired and wasted. They did not have adequate sterile mesh.

The incident at the airport delayed the start of the activity by 24 hours. Therefore, it is essential that, prior to carrying out any mission, the hospital (Dr. Mwitta or the hospital management, have a copy of all the clinical consumables and medications and anesthetic drugs) that the team is going to carry, including their expiration date if they have one. It is highly probable that if they arrive in Nairobi on Saturday or Sunday, there will not be customs officials with the capacity to make decisions and resolve the problem, with all the problems that this entails.

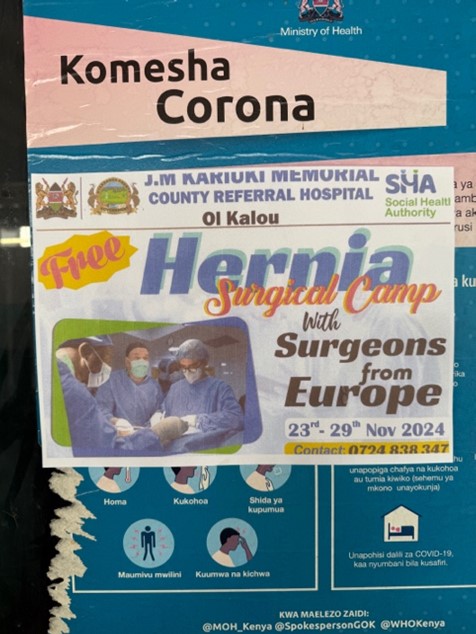

The other major problem that we detected is the lack of patients. Dr. Mwitta, as he told us, carried out an information campaign about the mission in public schools, markets and the hospital itself, since he found out several months before the mission was to take place, but in the end he was only able to recruit fewer than 60 patients. The efficiency of missions with few patients must be assessed, which make the personal and economic effort of each volunteer worthwhile.

We must thank the personal effort of Dr. Mwitta, a local surgeon, who with only one local assistant surgeon, carries out all the care of the patients and the urgent and scheduled surgery that arises, but it is difficult for him alone to also organize missions and recruit patients. This is a situation to be assessed in the future.

For the team’s stay in Gatundu, the team stayed in a hotel (Maxland Hotel) near Nairobi (45 minutes by van), comfortable, in single or double rooms and with breakfast included, at a very reasonable price. Local logistics, hotel reservations and transfers from the airport to the hotel and vice versa, and daily transfers from the hotel to the hospital (35 minutes) were organized by Dr. Mwitta and the hospital at no cost to the team.

The hotel is located in a shopping center at the foot of the highway where there are several fast food and local restaurants and a well-stocked supermarket. It is the best accommodation option for future missions.

Our recommendations for future missions would be:

1.- Send Dr. Mwita a list of all the clinic material, medicaments and anesthetics drugs that you are going to take well in advance, so that he can manage their authorization by the customs officials (Highly unlikely due to local idiosyncrasies).

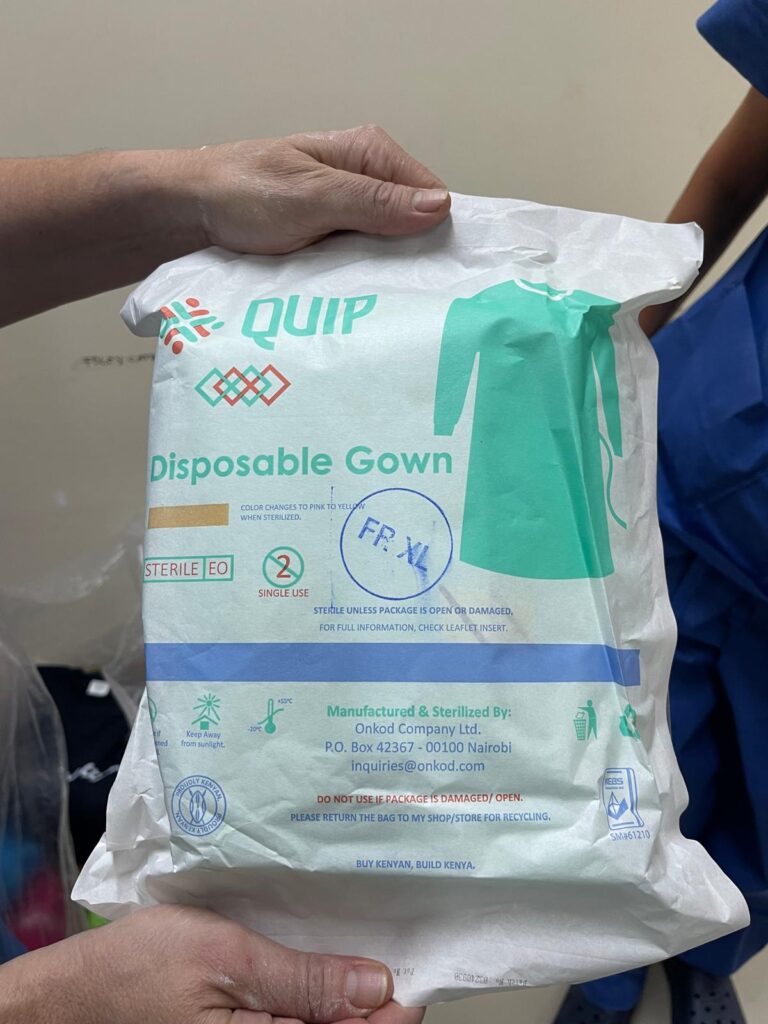

2.- Take plenty of surgical gowns, surgical gloves and surgical drapes. As we took few due to their volume and weight, we had to buy from a local supplier, since the hospital did not have enough units and they were reserved for emergency cases. We spent 500 dollars and in the end there were not enough units.

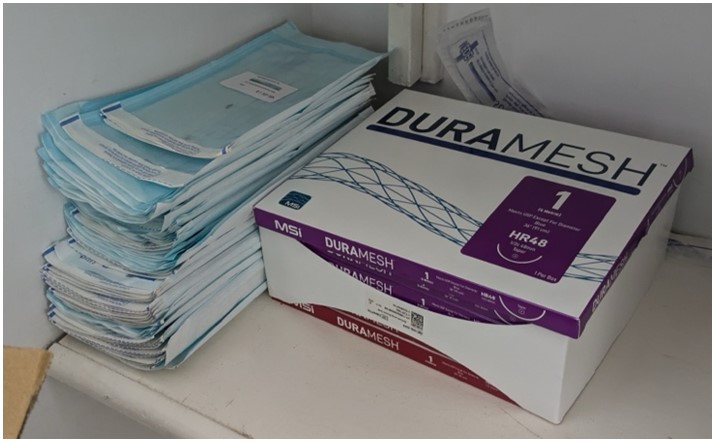

3.- Bring a supply of mesh for hernia repair. Our team brought 200 units of LDPE mesh, provided by Dr. Kingsnorth, already sterile and individually packaged. We left about 50 units at the hospital for future missions. It makes no sense to leave more because their sterilization date expires and they do not have gas sterilization, which is essential for mesh.

4.- The surgical instruments are abundant, but they are sequestered, and very disorganized. They always have to ask Dr. Mwitta for permission to use them, and the first two days we worked very precariously. This is an issue that needs to be improved directly, indicating the needs to Dr. Mwitta, so he has them ready.

5.- The drugs and anesthetic material are scarce, so we advise future teams to be well supplied with them, according to the preferences of each anesthesia team. The two pieces of equipment are basic but work without problems. There was only one problem one day due to a power cut, which took a while to resolve (it required the intervention of the local electrician and a me who indicated where the problem could be).

6.- Patient recruitment must be done well in advance, by the surgeons and hospital staff, otherwise there will not be enough patients to be able to operate on the 5 days.

7.- The team’s accommodation has been comfortable throughout the week and the transfer to and from the hospital well resolved from the hospital and at no cost to the team.

8.- Excellent collaboration and help from Dr. Mwitta and his local assistant, and adequate from the auxiliary staff, although after 8:00 p.m., it is convenient to finish the activity, because they start to get impatient….

Daily we started at 9 a.m. and finished at approximately 8 p.m. The hospital provided breakfast, coffee, tea and some pastries mid-morning and lunch at about 2 p.m.

I hope that this information and reflections will be helpful for the organization and execution of future missions. I am sending you some photographs. See you later.

Enrique Navarrete de Cárcer

Spanish team Hernia International, team lider